Eleanor Farjeon and the South Downs National Park

August 13, 2020

As the National Park marks its 10th anniversary, Dr Heloise Coffey remembers a writer whose life became inextricably linked to this unique area of the British countryside.

If the children’s writer and poet Eleanor Farjeon were alive today, there is little doubt that she would be celebrating the anniversary of the South Downs becoming a National Park. Farjeon is probably best known for having written the words for the hymn ‘Morning Has Broken’. She is believed to have been inspired by a beautiful morning in Alfriston, the East Sussex village on the South Downs Way.

Farjeon first developed a love of the South Downs, and of walking, through her friendship with the poet Edward Thomas in the years leading up to the First World War. Thomas lived in Steep in what is now the Hampshire stretch of the National Park.

At different times, Farjeon lived in both West and East Sussex: first in West Sussex in the hamlet of Houghton near Arundel where she rented a thatched property called ‘The End Cottage’ on Mucky Lane, (since renamed the more salubrious-sounding South Lane). She came here when struggling to come to terms with her grief after Thomas’s death on the Western Front in 1917. Later, during the Second World War, she rented a cottage in East Sussex called ‘The Hammonds’ in Laughton, near Firle.

In 1937, Eleanor Farjeon wrote ‘Elise Piddock Skips in Her Sleep’ in which the young heroine, Elise Piddock, lives in the village of Glynde at the foot of Mount Caburn, near Lewes. Although set in East Sussex, its main character was inspired by a little girl called Elsie who would skip near Farjeon’s home on Mucky Lane in Houghton. The fictitious Elsie Piddock learns to skip at the age of just three, using her father’s braces, quickly becoming a remarkable skipper. She is so good that she comes to the attention of the local fairies who, it turns out, also love to skip. They take her under their (tiny) wings, teach her their skipping steps, and give her a skipping rope with fairy powers. Years pass, Elise becomes an old woman, and a rich lord buys the estate on which Mount Caburn sits. He plans to ‘shut up footpaths’, ‘destroy rights of way’ and steal the long-held ‘common rights’ of the locals, including the age-old tradition of skipping up on the hill in a new moon. As if that weren’t bad enough, he draws up plans to build factories in the place where generations of little girls, like Elsie, had learnt to skip.

The locals are allowed one last night on Mount Caburn. The agreement from his lordship is that, when the skipping stops, the first brick of the first factory will be laid. But he hasn’t bargained for Elsie Piddock. Although now an old woman, Elsie starts to skip with the fairy skipping rope and skips and skips and skips. And never stops. In fact, she’s probably still skipping there still, saving Mount Caburn and the surrounding countryside.

Eleanor Farjeon’s story is more than just a charming modern-day fable – with skipping rhymes evocative of playground games of yesteryear – it is also quietly radical. In her hands, walkers’ rights become skippers’ right; the right to roam becomes the right to skip. Here was an author who not only wrote about the South Downs, but walked them; lived them. She would set off from her thatched cottage in Houghton and follow paths which now form part of the South Downs Way.

Farjeon would have cut an eccentric figure in the early years of the 20th Century: a woman clutching a shillelagh, a knapsack on her back, smoking a clay pipe and sometimes wearing a Russian peasant-dress made of coarse linen she’d bought at the height of the craze for Russian ballet. She thought of herself as quite a shy and bookish person, lacking in confidence – she once described herself as looking like a ‘cheerful suet pudding’ – but walking out on the Downs brought her out of herself and boosted her self-belief.

By 1916 she was ‘rambling all over Sussex’. Covering many of the chalk paths and byways criss-crossing the South Downs, Farjeon would pick up friends and acquaintances, old and new, along the way.

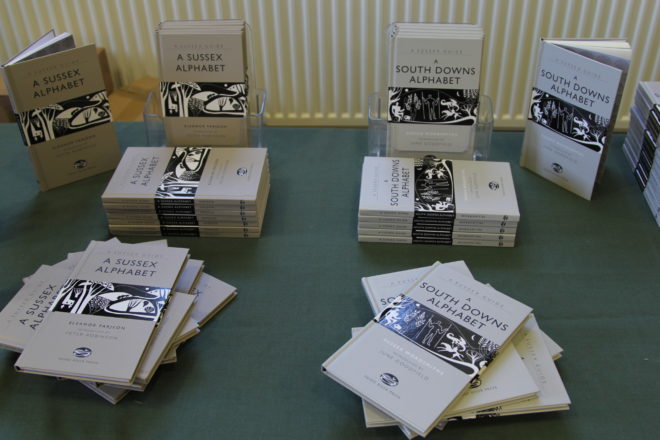

She would compose poems, stories and songs as she walked. Her rambles inspired the poem ‘All the Way to Alfriston’ recalling a fifty-mile walk she took, starting from Chichester. It describes the villages, their church bells echoing along ‘the running downs’; the abundance of wild flowers. It is a snapshot of the Downs a hundred years ago, brought vividly to life through words. Then came the anthology A Sussex Alphabet. First published in 1924, it consists of short poems, one for each letter of the alphabet, celebrating the uniqueness of the South Downs: the rivers (O for Ouse), the birdlife (N for Nightingale), the ancient history (L for the Long Man of Wilmington), and the distinctive geology (F for Flint). Even the South Down sheep, originally bred in Firle, get a mention.

Farjeon’s life and writings still have relevance today. There is overwhelming evidence that ‘getting out into nature’ can boost health, happiness and confidence, a fact amplified by the recent Covid-19 pandemic. Farejon understood the importance of experiencing the countryside first-hand in order to value it. She knew that if you know the name of, say, a wildflower or a bird or a tree, you are more likely to care about it and to want to safeguard it for future generations.

Dr Heloise Coffey currently lives on the Kent/Sussex border, having lived in East Sussex for many years. A rare first edition of Eleanor Farjeon’s “A Sussex Alphabet” was presented to the National Park Authority in 2018 by Dr Peter Robinson, of The Write House, as part of an inspiring project “The South Downs Alphabet”, supported by Dr June Goodfield.